Saturday, March 4th 2017

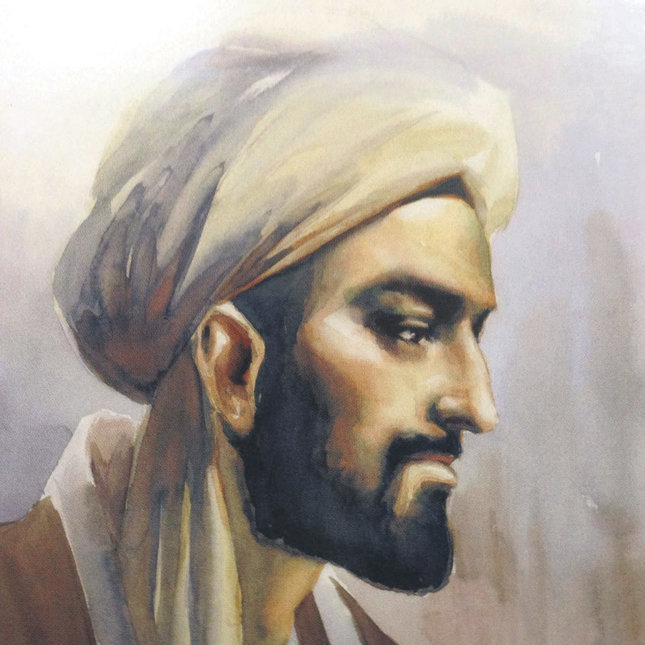

Known as the forerunner of the modern disciplines of sociology and demography, Ibn Khaldun was an Arabic scholar who was born into the rich Andalusian cultural era, whose wisdom has been shadowed by the Orientalist interventions and manipulation in the Islamic world.

There are two well-known distinctions in the history of Islamic sciences: “Positive sciences” and “traditional sciences.” “Tafsir,””fiqh” and “hadith” are traditional sciences and mathematics, while astronomy, geography and the like are considered positive sciences. Popular opinion suggests that there has been a major diversion in the history of Islamic sciences that caused the positive sciences to be dominated by the traditional sciences, which resulted in Muslims simply repeating established thought instead of creating new thought. We see the first evidence of this trend in the 17th century, but it has continued well into the 20th century. Orientalists were able to persuade the Muslim masses that no intellectual evolution could be achieved after Averroes (Ibn Rüşd).

However when the history of the Islamic sciences is reviewed, it is obvious that positive sciences have indeed continued and that popular opinion to the contrary is wrong. If positive sciences were abandoned in the 11th century, how were Muslims able to conserve their hegemony over that 700-800 year period? Orientalists have tried to down play the role of positive science by pushing the militant groups of Muslims to the forefront, but this does not explain how the Islamic “ummah” — who governed Asia and Africa completely as well as Europe to a considerable extent — achieved this without using positive sciences. It is true that the countries were conquered through warfare, but they were governed by wisdom and science.

Ibn Khaldun was a person who was completely focused on this subject. He asked himself: How do civilizations exist and decline? Ibn Khaldun tried to study this phenomenon through a methodological history, which he named “Umran al-Alam” in his famous work “Muqaddimah.” Orientalist fanaticism wants us to regard him as a unique star working with self-proclaimed wisdom, rather than a successor of the crafts of both positive and traditional sciences — portraying him as a precursor to the Western-style sciences instead. Ibn Khaldun has been called a proto-Marx or proto-Weber as though he was not the successor of thousands of historians, theologians, glossators, “muhaddises” — narrators of Prophet Mohammed’s words, poets, dialecticians and mathematicians, who all existed in the history of Islamic sciences. Needless to say, Orientalists have put forth both a slanted and prejudiced view of Ibn Khaldun.

Ibn Khaldun is one of the most approachable people in the history of the Islamic sciences. His work is self-explanatory. Similar to his work, his personality, scientific method and biography are also very clear. Our primary guides to the life and theories of Ibn Khaldun are his own works: “Iberian History,” the famous “Muqaddimah” — his self-written biography, his booklet about Sufism, “Şifaü’s” (“Sail”), as well as a range of booklets about logic, mathematics and poetry. These works, though not numerous, have been studied for centuries and have greatly influenced Ottoman-Turkish thought.

When modern-Orientalist theologians and political scientists analyze Ibn Khaldun, they often compare his views about society and civilization to Aristo, Plato, Farabi and Avicenna. These are important subjects of course, but almost no one has considered Ibn Khaldun within his own work and scope — especially in the analysis in Turkey. Recently, it has been determined that Ibn Khaldun has been well-known in Turkey since the 16th and 17th centuries, but no one has focused on his works independently from the classic Orientalist standpoint.

In reality, Ibn Khaldun was the son of a disintegrating civilization. His family was a known Andalucian family and migrated to North Africa, specifically Tunisia, at the end of 12th century. Ibn Khaldun started his story from a historical- sociological point of view. His writing of his own biography through telling his family’s historical destiny was a clear sign as to how his mind worked. It can be said, like Ibn Khaldun, every person benefits from the destiny of their family, lineage and community in which we live. Where we were born, which language we speak, where we live and are educated are all products of our educational context and the history of our families.

The most interesting biographical information Khaldun shared detailed his unique education: Quran recitation, Quran calligraphy, hadith, prophetic biography, Maliki Islamic law, poetry, literature, history and math, among other subjects. When we consider the disciplines he was taught, a high level of 14th century Islamic science content is evident.

After completing his education, Ibn Khaldun began working as clerk, later becoming a “kadi,” a Muslim judge. Within Muslim society, kadis were independent judges and carried out important duties for educational and bureaucratic matters. They sometimes played important roles in city administration. Khaldun was such a magnificent kadi that he was made the principal Maliki kadi for Egypt during the peak of his career. After all, he was a great master and scholar of traditional sciences.

Here we have come to a critical point in our argument about whether the dichotomy of positive sciences and traditional sciences is valid or not. Indeed, traces of the observations made during his visits to North Africa and Andalusia as a kadi are obvious in his historical methodology. If he had lived in only one city, such a broad knowledge and the experience of “umran” would not have been possible. Disordered Muslim cities of the 11th century lead Ibn Khaldun to reinterpret history and his famous methodology arose from this.

However, it is believed that the theories of Ibn Khaldun did not have much effect on Andalusia and North Africa, which were the subjects of his science, and in the end, he had little influence on this region of the Islamic world. While Ibn Khaldun was writing his works, the hegemony and the centrality of the Islamic world was shifting to the Ottoman lands, Anatolia. Which leads us to our next questions: When were the Ottomans rising? When was the decline of the North African Arabs?

Ibn Khaldun was born in the first half of 14th century in 1332 and died early in the 15th century, in 1406. Timur was reigning at the time of his death. The next two centuries would witness the rise of the Ottoman Empire, as well as its dominance over neighboring Islamic countries and most of Europe.

After the Ottomans established their empire, Ibn Khaldun’s writing and theories caught their attention. Kemalpaşazade (1468-1534) — Ottoman “shaykh al-Islam” and historian — is recognized as the first historian to document the influence Ibn Khaldun in history and sociological methodology. Additionally, a certain amount of Ibn Khaldun’s influence is seen in Katip Çelebi (1609-1657) and Naima (1655-1716), who were also important historians.

The Ottomans’ interest in Ibn Khaldun continued in the following years, and historians handed down this interest and knowledge to the historians of the Turkish Republican era. However, it is a fact that Orientalism has always tried to interrupt the process like a parasite. Orientalism took Ibn Khaldun out of his context as an Islamic scholar and bureaucrat and inserted him into a mold of remote Western thought. It is time to leave the artificial orientalist imitation behind and to read Ibn Khaldun for ourselves.

Source: Daily Sabah

Etiketa: ibn khaldun